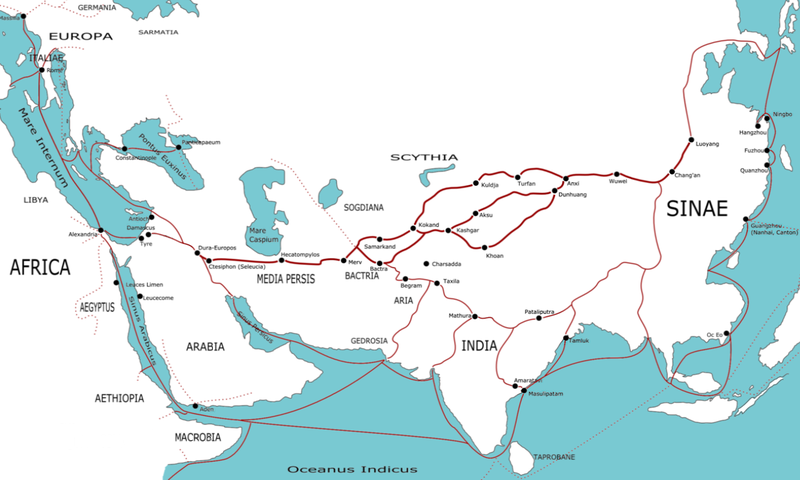

When archaeologists recently unearthed Roman glass dating back 1600 to 1900 years, the news went around the globe. But it does not come to a surprise that trade relations between Asia and Europe have been deep for a long time. In the amazing old town of Damascus, Syria one can still today get a feel of the prosperity that this trade brought to the ancient cities along the road. It still surpasses our understanding how much this trade influenced culture and societies on both sides of the continent. 500 years ago this route got blocked, and what seemed like an economic disaster forced people to literally look beyond their horizons and reinvent themselves. I am telling this story because it largely shaped the history of Hong Kong and Macau in particular, and gives us a better understanding of why Hong Kong is the way it is, and where trade might be heading to.

We have little information about the experiences and stories of those that traveled the silk road. They were traders, more occupied with their daily business and security rather than the historic implications of their actions. It is also difficult to find out how far individuals traveled on the silk road, compared with how far their products went around the world. With products being exported thousands of kilometers afar, the arts and crafts mixed, most notably in Persia, where Greco-Buddhist Art became a dominant stream.

But ideas got exchanged as well. The teachings of Buddhism followed the Silk Road and it is not too unreasonable to believe that they heavily influenced the teachings of spiritual leaders like Jesus of Nazareth or Muhammad of Mecca.

In the following centuries empires in Europe came and went, and in China one dynasty followed the other. Among the notable inventions to cross the Silk Road was Gunpowder around the 13th century. Surprisingly, not all Chinese inventions made it to Europe, for example paper money, the compass or the printing press. Trade was for a long time reduced to goods with little political interest, like cloths, silk, spices or jewelry. It is difficult to reconstruct, but even back then, in the absence of tight border controls and efficient bureaucracy, trade was not as free as we sometimes imagine it. Heavy duties and taxes at every bridge, government ownership over inventions, capital and technology make it difficult to export certain goods. Maybe gunpowder only made it out of the country because it is easier to smuggle than a printing press?

Around the 13th century, the silk road experienced a strong increase in trade while most of Asia was under Mongol rule. They had little political interests and tried to maintain their nomadic lifestyle as best as they could, avoiding moving into palaces and forts and establishing a costly bureaucracy. It was then that Marco Polo allegedly reached China by Land, and brought back the first written impressions of the far east. In the late 14th century, the black death traveled along the silk road to Asia, and trade slowed down, the Mongols lost control over China and in Europe states fought bloody wars. Around 1400, the route became unpassable.

As European royals were deprived of their precious luxury goods, for maybe the first time in history, they had to look for ways to rethink the old, and to everyone’s surprise succeeded. What happened was the beginning of modern times and the first step out of medieval darkness. When the silk road closed, China and Europe were technologically quite equal, when the two reestablished trade 200 years later, they were unequal partners.

As European king’s were competing over who could reach Asia first via sea, they eventually discovered the Americas and Australia, sailed around Africa and settled in Asia within just about 200 years. Ever since the trading routes were established via sea, most of the goods have been shipped around the south African capes or the Suez Canal to the European ports. And as the silk road had become unused, China’s trade centers changed. The largest Chinese cities in the year 1500 are estimated to be 北京 Beijing (with 600,000 people, the largest in the world at that time), 杭州 Hangzhou (250,000) and 廣州 Guangzhou (150,000), all cities along inner-Chinese trade routes. They stayed the largest Chinese cities until well in the 1800s. Today 上海 Shanghai (25 mio), Beijing (20 mio) and 天津 Tianjing (10 mio) are the largest cities, and only Beijing is not directly by the sea.

Hong Kong is currently the third largest container ports in the world with 24 million shipped TEUs. Shenzhen and Guangzhou are also in the top 10, making the Pearl River Delta the maybe busiest area in the world.

Still today, with the cold war being over and during a time of until now unknown peace and prosperity, trade along the former silk road is marginal. In fact, we might assume that the silk road is only open again since April 4, 2011.

On that day a freighter train operated by Deutsche Bahn Schenker arrived in Duisburg from 重慶 Chongqing, completing a 13 day journey along 12,000km of rail through China, Kazakhstan, Russia, Belarus, Poland and Germany. It transports largely personal computers and accessories like screens. Hewlett-Packard, Foxconn (Apple) and Cisco have long produced in the area, and Acer added itself to that list just one month after the completion of the rail link. These goods have become increasingly costly to ship via sea, due to the increased insurance premiums against piracy. But more importantly, computers produced by HP or Acer are today sold with thousands of customization options. Customers in Europe do rarely want to wait the 30 days that it takes to truck a computer to Hong Kong or Guangzhou, from where it needs to be shipped via cargo ship. Customers are also rarely willing to pay the hefty fees for airlifting the computers, and so the new rail link offers a fast enough and yet cheap enough choice.

Such rail links however are much more vulnerable to shifts in political climate and public security. Having a rail link is no doubt a huge investment, and with these gigantic sunk costs China and Europe fear the blackmail and instability of the transit states. Just like with the silk road in the 13th century, the silicon road of the 21st century will be prone to wars, violence instability in the countries that it passes through, most notably the political wild cards Belarus and Kazakhstan. But it also removes the ability of other states, most importantly Egypt, to blackmail global trade using the Suez Canal. The Suez Canal now charges around 1 million US$ for a large freighter to cross the channel, a significant cost. China has for a long time looked for time saving alternatives to this route, and though going all around the Cape might be easy and without larger investments, it still despite the large Suez Canal fees is the more expensive option.

Giving this, the Chongqing – Duisburg rail link seems practical, and so does the proposed link between Eilat and Ashdod in Israel, linking the Red and the Med with a 350km rail.